How weak Europe is politically! A kingdom of the kind thrown up by the history of the world – from the Roman to the American to the Chinese – was never near European shores, and for historical reasons as well. The continent of Europe was distinguished for ages by fragmentation into petty principalities. And the marks left by history have enormous powers of endurance. The happy and successful era of European integration has been far too brief for this deep-seated legacy of discord to be brought to a permanent end.

But because the founders of the new Europe wanted to neutralise this heritage with all the force they could muster, they pressed down hard on it with the millstone of the EEC (and later the EU). Indeed, and at least up to Helmut Kohl, the iron rule was that every EU member state was to be equally important, no matter how big or small. Multifaceted and egalitarian was to be the new historical image. However, as suggested already by talk of the Franco-German engine or of the Carolingian foundations of the enterprise, the new Europe was in fact, away from its centre, an imaginary entity. It is this stubborn centricity, exceedingly well represented in Brussels, that is making the EU wobble, and not just since yesterday.

One feels it everywhere, and especially along the borderlands. This first became evident a little while ago in Hungary, with its massive turn towards nationalism under Viktor Orbán's Fidesz party. The country, which is one of the newer members of the EU club, is playing the Magyar card, and its government is striking up a fanfare of national awakening steeped in Hungarian history that will not resonate at all with the rationally humming management of Europe that Brussels knows best.

Finland still has it pretty good

Hungary's new constitution, drafted and sealed by the ruling majority without referral to any constitutional procedure, is a foreign body in the European constitutional ensemble. A highly emotional preamble swelling with pride in Hungary’s history anchors the Republic – which it remains, so far! – in the 11th Century, bound to the imperial crown, Christianity, and (a large) family. Hungary demonstrates that along the edges of the EU, under the protection of the EU and within the legal confines of the EU, ideas other than those promulgated by the Brussels court can gain ground.

But trouble for Brussels is brewing even among Europe’s model students. The Netherlands proved pesky some time ago, and the Finns have just opened another chapter in this new European disorder. The Finns are not known as extremists. For decades they worked hard at an odd system of government succession in which three parties governed in an almost regular cycle, which meant disputes among the major parties were always settled amicably.

After all, the punching bag of today was the bedfellow of tomorrow. Despite Nokia’s downward turn, the PISA-wonderland of Finland still has it pretty good. Nevertheless, an apparently up-and-coming party that calls itself the True Finns or, more precisely, Ordinary Finns, which has succeeded in becoming the third-strongest party in the country with rather more rightist than leftist populist elements, will now likely be in the government. A sudden furore that can break out even in the most peaceful and civil of families?

The deplorable state of the EU

It was quickly agreed that it would be the well-stretched protective shield that would handle such rebellions. For somewhere in the undergrowth of every European people slumbers a national obstinacy that sees its neighbours more as expensive boarders than allies. That may be true, but it still does not explain what is happening.

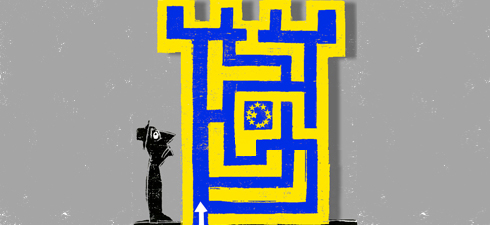

Everywhere in Europe there is, in principle, a willingness to take responsibility for, and to pay for, an enlightened EU. Europe is not hostile to the Greeks. But the Europeans do not want European progress forever presented to them as a kind of well-oiled machinery to which there is no alternative and that is so complex in its workings that only a grown-up like Brussels can run it – the little people themselves must stay outside the building.

Recently the philosopher Jürgen Habermas complained again of the “deplorable state” of the EU. While he stresses the need for a democratic renewal for Europe, he overestimates the ability of Europeans to recreate a new Europe with a purpose. In one thing, though, he is right: “European integration, which was always pushed ahead with over the heads of the people, has now reached a dead end, for it cannot carry on without being switched over from the usual administrative mode to one that involves greater participation by the people.”

Translated from the German by Anton Baer

Opinion

Habermas against the elites

In an article in theSüddeutsche Zeitung, Jürgen Habermas voices concerns over the “lamentable state” of the European Union. The German philosopher regrets that national budgets and national parliaments are relegated to rubber-stamping the decisions of the European Commission, while European citizens rally round their own leaders in struggles across the European stage in which their “heroes of the nation take on ‘the others’”. The consequence: the EU’s reputation is clouding over even in the supposed Europhile, Germany. And the elites are sticking their heads in the sand.

For Habermas, three reasons explain the lack of steam in the European project: the rediscovery of the nation state by Germany, which is now looking inwards; the manipulation of European elections and referendums to suit opportunistic national ambitions; and collusion between the political class and the media, which treat the euro crisis only in their highly specialised business pages and ignore the political dimension. “But perhaps in looking up at the political and media elites, we are looking the wrong way,” says Habermas. “The motivation that is lacking may emerge from below, from civil society... And for that, the recent protests in Germany, such as Stuttgart 21, may serve as examples.”

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!