More than one journalist has dreams about creating a narrative so powerful it outlasts the present and shapes the public perception about an institution. Few stories about the EU have been as persistent over the past decades as the tale of the 'bendy banana law', which first made its appearance in the UK in a story in The Sun in September 1994.

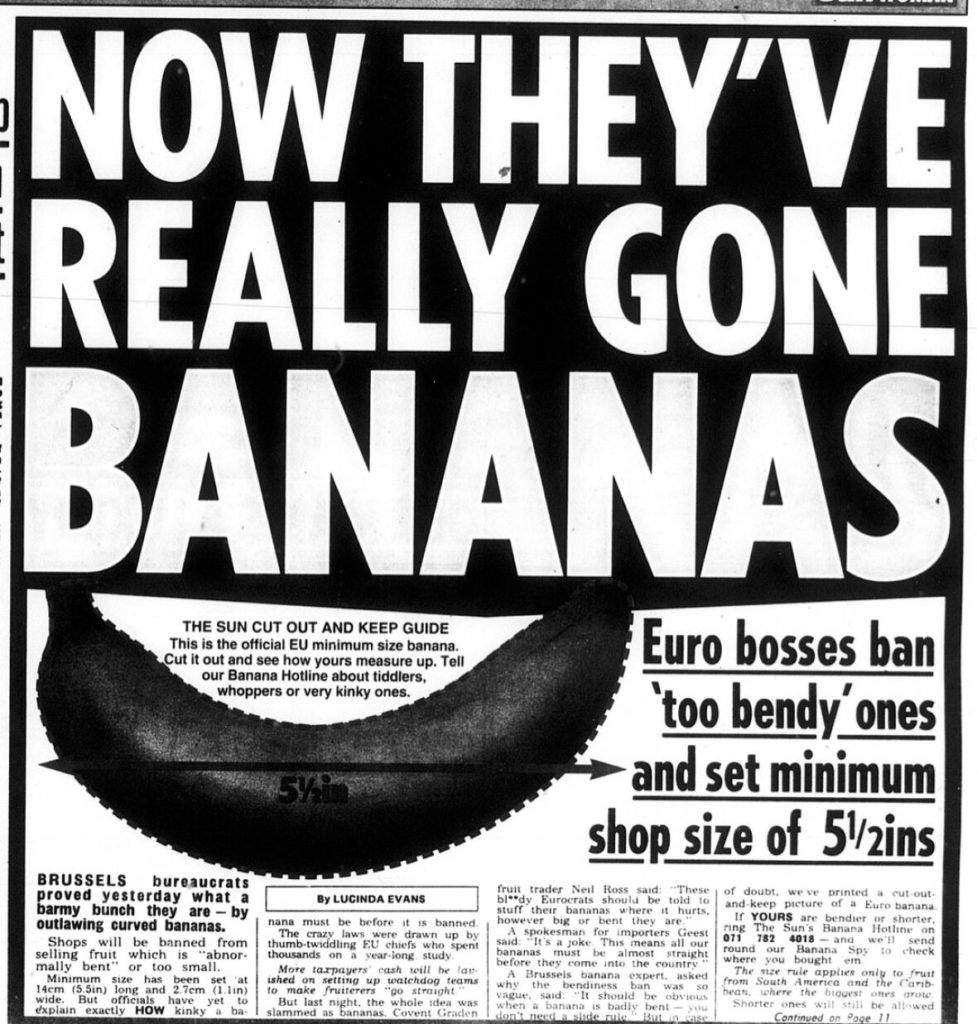

According to the article written by journalist Lucinda Evans, “Brussels bureaucrats” created a pointless law that would “outlaw curbed bananas”. “The crazy laws were drawn up by the thumb-twiddling EU chiefs, who spent thousands on a year-long study”, the story says. The Sun's headline screams: “Now they've really gone bananas”. The Daily Mirror, Daily Mail and Daily Express followed-up with similar stories about bendy bananas.

Although the narrative about a pointless law dreamed up by out-of-control bureaucrats was almost immediately fact-checked and contextualized by other journalists, the impression it created persists to this day in tabloid stories and as a far-right talking point.

Boris Johnson repeatedly cited 'crazy' EU rules about the shape of bananas in 2016 to justify his vote for leave in the Brexit referendum. The 'bendy banana' has become a folk-tale of brazen bureaucracy in 'bonkers Brussels'. It set the standard for similar storylines, many of which were intended to fan the outrage about a European Union supposedly disconnected from common reality. The narrative about silly EU rules on bent bananas, crooked cucumbers and other regulatory nuisances played a crucial role in bringing about the UK's exit from the EU.

Yet peeling away the outer layer of the mythological banana and having a look at what actually went on in the European Commission back in 1994, a different, more complex story emerges. The real story behind the 1994 banana law lies in the Commission archives. It has been hidden in a stack of 41 documents, mostly faxes and letters typewriter-written in French. The Commission papers, dormant for over two decades, were recently unearthed by the author through a request under the EU's freedom-of-information law. They give a rare insight into the process of law-making and who is involved in it.

‘Curvature of the fingers’

In truth, the European Union does have a banana bill. Regulation 2257/94 decrees that bananas should meet minimum quality standards such as being 'free from malformation or abnormal curvature of the fingers'. The regulation does not outright ban bendy bananas. Rather, it restricts their sale to certain trade categories. According to the law, bananas of the “extra” category must have no defects, but Class 1 bananas may have "slight defects of shape" and Class 2 bananas may have additional "defects of shape". This includes, presumably, defects such as “abnormal curvature”.

As an article in the Independent only a few days after the Sun story pointed out, these rules were neither arbitrary nor uncalled-for, as they intended importing businesses to 'get value for their money' while preventing EU agricultural subsidies being wasted on poor produce. But at that point, the tabloid narrative of bureaucratic overreach by “thumb-twiddling EU chief” had been set. “The daftest of EU rules has finally become British law”, the Express reported on a later occasion.

“Brussels grey men”

Following another, competing storyline set out in EU press releases, establishment figures such as former cabinet minister and Tory Europhile Kenneth Clarke have tried to re-cast regulation coming from the European Union as vital, common-sense law-making. Laws allegedly imposed on the UK by “grey men” in Brussels in reality were done in the interest of “consumer protection, product quality, environmental rules … all of this kind of thing“, Clarke told a Canadian TV channel in 2016. In the mid-Nineties, Commission press office in London set up a rapid response system to counter negative stories about the EU in the British press. It produced over 400 rebuttals of “Euromyths”.

Alas, what really went on in 1994 neither fits comfortable with the tabloid narrative about “bonkers Brussels” nor the one about enlightened Eurocrats working in the public interest. The true banana story is one from the coalface of European law-making. It offers a glimpse into a world of industry interests and back-room dealing. In the real Brussels of 1994, as opposed to the tabloid fantasy-land, it was not just officials who were crazy about regulating bananas, but corporate lobbyists and government officials.

Here are the facts.

Far from being a fever-dream of crazed bureaucrats, the banana regulation was requested by COPA, an interest group of European farmers, as the Commission pointed out in an answer to an MEP's question back in 1994. The intention of the law was to improve the quality of bananas grown within the EU, in places like the tropical overseas territories of France. Higher standards were to make European bananas competitive with products from outside the EU, the Commission said in a newly released letter.

Following the request by the trade group, the Commission set up a working group of experts to, literally, work out the kinks of banana law. While the experts met between 1993 and 1994, the Commission was lobbied by trade groups. The European Association of Banana Trade Association (ECBTA) alone sent no less than eight letters to the Commission.

“It would certainly allow for quicker results if the ECBTA were allowed to put a draft on the negotiating table that is accepted by our members”, a trade representative writes in the first letter. Setting up a working group to overcome differences among its corporate members, the trade association engaged in lengthy bartering with the Commission. In its letters, the group made detailed suggestions down to the size and permissible defects of the fruit.In due time, the lobbyists' suggestions had a strong impact on the final outcome of the law.

A French suggestion

Member states lobbied as well, as the documents show. A major point of contention between the member states, the documents suggests, was whether to regulate only unripe, green bananas or all traded banana. France was by far the most active country. The French government sent no less than six letters and faxes to Brussels, which were declassified by the Commission only after getting the green light from Paris.

A missive from January 1994 contains detailed suggestions and included the complete text of a 1975 French law which stated, among other things, that bananas of the highest quality may not show any “malformation or abnormal curvature of the fingers”. Six weeks later, officials included almost identical phrasing into a working document on the new law. They sent their suggestion to the Cabinet of their political master, Luxembourgish agricultural Commissioner René Steichen. Later letters from the German and Spanish governments support banning bananas with abnormal curvature.

The documents do not make it entirely clear if the suggestion to ban wrongly formed bananas first came from the French, but clearly the fax from Paris contains the first mention of “abnormally curved” fruit in the documents. This fits a pattern in EU law-making as “lots of existing standards from individual countries are adopted by the EU for the European market”, former Commission official Charlie Pownall says. Meanwhile, the UK appeared less then enthusiastic about the proposals. “First of all, I must emphasise that the UK does not favour an unnecessarily complex set of standards”, the fax from Whitehall to Brussels states. “We would prefer a simple standard which augmented the standards already applied by traders and retailers.” The British objected in particular to “any system of classification which links quality to size”.

The government, then led by the deregulation-happy Tory prime minister John Major, was “committed to removing unnecessary regulatory requirements”, the missive stated. “This is an issue on which we feel strongly.”

Alas, the British government did not feel strongly enough about the process to explain or defend it in public. Major and his government apart from the more Europhile foreign office “did little to counter any of these stories”, says Pownall, who worked as press officer for the EU Commission in London in the early 90ies. Adding to the lack of understanding was that British papers rarely covered how European laws were made, he says. “The political process did not get reported on.”

Bananas and prawn cocktail crips

In the end, British misgivings about the law did not stop it from entering into law on September 16, 1994. The final version set out minimum requirements for bananas that were heavily influenced by the wishes of certain EU governments and banana traders, even if the final result was more detailed than they had asked for. In effect, it was the law that lobbyists and governments wrote.

For all the years of obsessing about 'bendy bananas', little about the making or reasons for the law got reported in the British press. A possible reason for that is that, then as now, much EU law-making happens behind closed doors. That makes it difficult and labour-intensive to report on. Instead, British journalists kept pressing on with stories about the EU allegedly banning prawn cocktail-flavoured crisps or mince pies.

Boris Johnson, then correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, added to the slew of dubious reporting with a questionable story on a supposed Italian demands for smaller condoms. But being accused of 'making it up as he went along' has not dissuaded Johnson from making false claims about EU red tape up until his election as prime minister. After all, he gets away with it and the British people have excepted the narrative of out-of-control Eurocrats as fact. However complex the true story might be, the narrative has stuck.

Read this story on EUobserver.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!