Close to 400,000 Poles are already working in Germany, some of them legally and others in the black economy. Tens of thousands have also found jobs in Austria. The Ministry for Labour and Social Policy has announced its official forecasts: starting on May 1, with the full opening of the labour markets in these two countries, a further 400,000 Poles are expected to seek work abroad [the newly opened labour markets will now be accessible to workers from Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia]. Those who choose to emigrate will not do so in a single immediate wave, instead the movement will likely be spread over the next four years.

According to data from the Polish Federation of Private Employers, Lewiatan, Polish workers are in high demand in both countries. The Germans need 30,000 IT specialists, a similar number of engineers, and around 50,000 people to care for the elderly, explains Lewiatan expert Monika Zakrzewska, who points out that doctors, construction workers, electricians, locksmiths, mechanics, confectioners, opticians, and hairdressers will all easily find jobs.

Over the last two months, in the voïvodies [provinces] of western Poland, German employers have been organising job fairs and publishing internet advertisements.

Like the experts at Lewiatan, the ministry for labour is intent on calming fears of a mass exodus similar to the one that took place in 2004, following Poland’s accession to the European Union.Unemployment is no longer as high, the most courageous and dynamic workers have already left the country, and relatively few Poles have a good command of German. Moreover, the specialists that are sought after by the Germans already have jobs in Poland so they do not need to leave, points out Monika Zakrzewska.

However, experts can sometimes be very wrong. In the run-up to accession, it was estimated that 40,000 Polish workers would emigrate to the UK. the real figure turned out to be ten times higher than expected.

An economist and demographer working at Warsaw’s Centre for International Relations, Professor Krystyna Iglicka, believes that this time around the number of people who want to leave Poland could exceed official forecasts. The signs are there to be seen: the Germans are intent on attracting the Poles with enticing job offers, and the residents of ‘Poland B’, which includes the country’s poorest regions, are eager to find work.

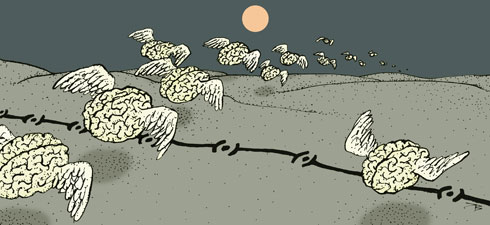

Poland can no longer sit idly by, while large numbers of its citizens settle for a life in exile. Over the last few years, the country has been marked by the biggest wave of emigration in its history: 800,000 Poles went abroad in the 19th century and one million left in the 1980s, but in the wake of accession to the EU, nearly two million Poles moved away from the country. Many sought a new life in England, where, according to figures from the National Statistics Office, 550,000 are currently working. Another 140,000 found jobs in Ireland, 90,000 in Italy, 80,000 in Spain, 50,000 in France, and 70,000 left the EU.

In times past, emigrants only had a basic education, but those who left in 2004 were typically young graduates. Starting out in jobs as dishwashers or house cleaners, most were simply hoping to earn a little money before returning home. But more often than not, what began as a short stay quickly turned into a longer period of exile that in many cases became permanent.

“This is a lost generation for us. Not because these young people are lacking in drive or talent, but because Poland loses theme definitively,” remarks Professor Iglicka. In her most recent report on emigration since 2004, she notes that Polish women who settle in the UK have a much higher fertility rate than those who opt to stay at home: 2.48 children per woman, which is far higher than the 1.84 rate for British women, or the rates for women in Indian or Bangladeshi immigrant communities. The explanation for this phenomenon is quite simple: giving birth and bringing up children is much easier in Great Britain, which has the advantage of better quality social security and health-care systems than the ones in Poland.

Worse still, those who decide to go home to Poland usually regret their choice when they find that no one is waiting for them with open arms. There are no jobs for them when they leave the country, and that remains the case when they return. At the same time, their experience of working abroad is hardly attractive to Polish employers, who are unimpressed by CVs that have remained unchanged for years (they can hardly claim credit for having worked as dishwashers or babysitters).

In many cases, the expectation that they will be able to return with an excellent command of English also turns out to be unfounded, because Poles living abroad tend to socialise with their compatriots and they rarely have time for language courses.

For those who come back, it is also important to have no illusions on the issue of salary: having earned an average of 9,000 zlotys [2,284 euros] abroad, on their return they are often offered as little as 1,500 [380.65 euros], notes Professor Krystyna Iglicka.

Very often they are disappointed and decide to leave again — perhaps in part because emigration has changed them. As sociologists have pointed out, people who have grown used to other cultures, to different colours and the sounds of different streets where multilingualism and multiculturalism are the norm, are likely to feel lost and even suffocated in Poland.

“We are not creating good living and working conditions for young people,” warns Professor Iglicka. “On the contrary, we are pushing them towards the door. Authorities in this country have grown used to emigration, which they see as a means for reducing unemployment. Their point of view is: if there is no work for young people, they can always leave! If and when they decide to come home, they will be the responsibility of future governments, who will also have to cope with the issue of emigration and the demographic problems it engenders. In the meantime, the current administration can rest easy.”

According to the Deloitte consultancy, 60 % of Polish students are prepared to leave Poland. They are convinced that they have no prospects in a country where the rate of unemployment among graduates from major universities stands at 24 percent.

View from Praque

Czechs want to go to Germany, too

“Germany needs of thousands of Czechs,” writes Lidové noviny on the eve of the fall of the last administrative barriers to job-seekers from central and eastern Europe. In Germany and Austria, as in the Czech Republic, there is a shortage in the technical trades. “But working abroad is not like it used to be,” the Prague paper notes. “Due to the strengthening of the Czech koruna and the high cost of living in our western neighbours, wages are no longer the stuff of fantasy.” Lidové noviny adds that working abroad will “be worth it for those who live near the border, for they will be able to take advantage of German wages and Czech expenses.”

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!