A television programme does not capture 30.21% of the national audience just because it is well made. If a programme is good from a professional point of view, it will be rewarded with ratings that are slightly above average. But to exceed 30%, it has to be an event. And for that to happen, the programme has to capture the spirit of the times and respond to deep-seated need in the country.

Italian television audiences have been overwhelmed by a terrible hunger for truth. Overnight, truth has become much more engaging than reality TV, and the ratings are there to prove it. After years of infotainment, of celebrities and Big Brother, the programmes that are enjoying the most success are the ones that focus on analysis and investigative reports. A breach has opened up, which has led to an increase in the demand for information. But beyond the sphere of television, if we take a look at Italian society, we can discern the reasons for this emerging televisual revolution.

As an audio-visual substitute for the grim reality of the average person’s life in Italy, we are routinely offered accounts of the glamourous existence of our Prime Minister, with his 20 properties and endless celebrity parties. Silvio Berlusconi has described Italy as prosperous country, because everyone has a mobile phone and the country’s marinas are thronged with yachts. If this method of portraying reality was based on statistics, it would examine a sample of ten people that included one who ate ten chickens, and conclude that everyone had one chicken each.

Italy - a civic and moral failure

The ruins of the gladiator’s house in Pompeii, the rubbish that is once again piling up in the streets of Naples, the flooding of Venice, and the earthquake victims in Aquila who are still waiting for their homes to be rebuilt constitute a more accurate metaphor for today’s Italy. Sitting on a pile of rubble and garbage, not only in real terms but also in a figurative sense, ours is a country that is wondering if there exists a system of values that could still make a difference.

It is in this atmosphere, which has much in common with The Last Days of Pompeii, that Fabio Fazio and Roberto Saviano’s programme takes on the mantle of civil society’s response to a political elite that has lost the trust of the people, who are offered a choice between morally bankrupt Berlusconism, a stagnant opposition, and abstentionism which is the only political cause that appears to be making any headway.

Vieni via con me (Come away with me) is basically a public service programme. It addresses the entire country and deals with topics designed to interest the widest possible audience. And as a public service, it offers a democratic forum for the analysis of events and universal values. That is the framework in which Vieni via con me should be understood. In a period where there are no longer any certainties, in which Italy appears as a civic and moral failure, it encourages us to take an inventory of what can still be saved and what we should be fighting. It is a programme that assumes the role of an event, because it responds to a real need in the country.

A repetitive force worthy of the rosary

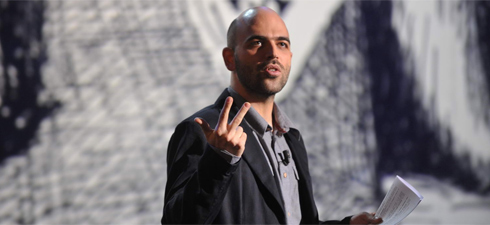

Within this framework, Vieni via con me functions like a ritual referendum on the future of the nation: Should we leave? Or should we stay? Is there anything that we can do to stay? And as a ritual it is made more powerful by the presence of an officiating celebrant in the shape of Roberto Saviano, a man who has come to symbolise the need for legality in a country where the law is relentlessly flouted. The programme is by no means perfect: on occasion it indulges in rhetoric, preaches to the converted, and presents well-known facts as though they were revelations. More often than not, it lacks the deep-level investigation which gave Saviano’s book, Gomorrah, its remarkable power.

It offers little in the way of breaking news or groundbreaking investigative reports, nor is there any real philosophical investigation of moral themes. The state of the country is presented in the form of lists and recurrent refrains, to the point where it aspires to the status of an endlessly repeated mantra. In Vieni via con me we encounter things profound and comical, superficial and absurd. But what is remarkable about its enumerative approach, which transforms news into a kind of liturgy, is its homgeneous impact on the public.

The real power of Vieni via con me is a function of this apparently banal repetition, and what appears to be its formal weakness is in fact its greatest strength. A liturgy cannot be new, because it is an invitation to prayer. And that it is why the programme seeks to present events in a format with a reassuring cadence and repetitive force worthy of the rosary.

Vieni via con me

Recipe for a runaway success

A sparsely decorated and largely empty set with no skimpily clad starlets or actors on promotional tours, no singers and hardly any music except for a few phrases from the Paolo Conte song Vieni via con me, but the show is a runaway success. The two men behind Italy’s latest television phenomenon are Roberto Saviano, author of the best selling investigation of the Neapolitan mafia, Gomorrah (who is now obliged to live under a permanent police escort), and Fabio Fazio, a veteran television presenter with a talent for putting a wide range of guests from the worlds of sports, the arts and politics at their ease. Everyone who appears on the show is invited to read a list: there are lists of reasons for leaving Italy, lists of reasons for staying, lists of pet hates and lists of left- and right-wing values. On occasion, the idea borrowed from Umberto Eco’s The Infinity of Lists appears naive or even tiresome, but most of the time it works. "The success of the show is partly political,” explains Fabio Fazio. “It is based on three things: Saviano’s reputation, the fact that it is a modern programme as opposed to a ritualised TV show where nothing every happens, and the Italian people’s desire for modernity. The tragedy of Italy is that the country is completely paralysed and stuck in a rut. " Philippe Ridet, Le Monde (extracts), Paris

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!