In a comparative analysis of mass protests, V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) ranks “the pro-democratic mobilisation in Belarus in 2020 among the 15 largest and longest mobilisations among more than 100 countries in 50 years. Even the Ukrainian mobilisation of 2014 and the Venezuelan mobilisation of 2017 are lower in some parameters to the Belarusian one”.

Belarusian society in 2020 demanded both an end to state violence and democratic reforms; however, the protests of that year did not bring about the desired result. Quite the reverse, in fact: the authoritarian regime has continued to strengthen its position. The methods used today by the state to tighten its hold on society bear traits typical of totalitarian regimes.

Even so, the suffocating atmosphere created by the political repressions does more than strengthen the feelings of insecurity, anxiety and fear among those who live in Belarus; it also demonstrates the fear of the regime itself, which continues to use unconcealed violence as virtually its only means of “interaction” with society.

Societies on a revolutionary course

“Is this a movement or a missed opportunity?” This is a question posed by Asef Bayat, a sociologist who has researched the Arab Spring, about the recent mass protests in Iran. This question links the 2022 protests in Iran with those in Belarus of two years earlier, as does the extent of public involvement in them.

In the first three months following the murder of the young woman Mahsa Amini by the Iranian police, two million Iranians – women as well as men – from all segments of society organised no fewer than 1,200 protest actions in over 160 towns and cities. Students of both tertiary institutions and secondary schools organised sit-in strikes; lawyers, preachers, professors, workers, sportsmen, doctors and artists publicly expressed support for the young people and joined the protests.

According to the leaked results of the sociological research conducted by the government of Iran in November 2020, 84% of Iranians viewed the protests positively. Participants in the protests – women formed one of the most prominent groups – were united by their pro-democracy demands. However, as is the case with Belarus, Iranian society is at present far removed from a “revolutionary situation”. Nevertheless, according to Bayat it is on a “revolutionary course”.

This means that a significant section of society continues to think, imagine, speak and act from the perspective of another, non-authoritarian future for their country. The reverse side of the coin is the conviction that sooner or later the ruling regime will collapse, that it is in fact doomed. “This is why any inconvenience – eg, a water shortage – is viewed as a failure of the regime, and any display of dissatisfaction – eg, because of a delay in paying wages – becomes a revolutionary act. It follows from this that the status quo is seen as a temporary phenomenon, and so changes are a matter of time.”, adds Asef Bayat.

He compares the point reached by the “revolutionary path” in today’s Iran with that attained by Polish society between 1981 and 1989, when martial law was introduced as a response to the unprecedented level of public activism that the independent trade union movement “Solidarity” had stirred up. “Solidarity” was registered in November 1980, and by March 1981 it had 10 million Poles as members. However, of no less importance for this public awakening was the fact that for the first time the workers were now joined by the intellectuals and the Church.

In the words of the Polish feminist theorist Ewa Majewska, the catalyst that brought about this public awakening was the opportunity to suddenly conceive a desire to participate in the country’s politics, to change them and to be involved in the process. The arrest in December 1981 of 3,000 of the most active participants of “Solidarity” and the total control of society established by the Polish regime led to the creation of an underground in the country in which women played a key role.

Shana Penn, author of an essay on the crucial role of women in the history of “Solidarity”, describes the underground in this way: “The underground became a frontier zone between private life and public life, between the past and the future, between tradition and democracy. It was the kind of intermediate space in which borders are erased, rules are weakened and changes occur.”

The meaning of “weak power”

The chief method of resistance during this period in Poland, according to Ewa Majewska, was “weak resistance”. Its determining features were implicit concepts and informal networks; an important part within it was played by individuals helping each other spontaneously, and it avoided direct confrontation with the regime.

Symbols and the way in which they were appropriated acquired huge significance in this struggle. Their appropriation enabled the resisters to make sense of what was going on in their own interests. This form of resistance demanded perseverance and strategies that unfold in everyday life, rather than exclusive or heroic acts. Finally: there were mistakes and weaknesses within these strategies, and it was crucial to recognise and analyse them, rather than seek to conceal them. Taken all together, these forms of resistance not only permitted the preservation of the spirit of “Solidarity”, but eventually came to provide an essential condition for the peaceful transition of power in Poland in 1989.

At the same time the “Solidarity” movement, during the time of its activity in the public sphere – ie, in the short period before the introduction of martial law – was sometimes seen in ways reminiscent of how the Belarusian protests of 2020 came to be regarded. For example, as early as 1983 the well-known Polish sociologist and political scientist Jadwiga Staniszkis observed that “Solidarity” was insufficiently political because of its concern with ethics. Discussions among lawyers as to whether or not the creation and activities of “Solidarity” constituted a revolution have not yet been concluded.

“Solidarity” did not dispute the most general aspects of socialist reality. For example: it is evident from the 21 demands of the so-called August agreement that its aim was not the overthrow of communism. Nevertheless, Zbigniew Kowalewski, someone involved with “Solidarity” right from its earliest days, has noted that, had the August demands been fully met, the political system that existed in Poland at the time would have been blown to bits.

In this connection Ewa Majewska makes use of Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia – counterspaces and a kind of effectively functioning utopia – which was being developed by “Solidarity” in the very heart of Polish state communism in factories and other enterprises. In this sense, “it was not simply a protest, a reform or an alternative. ‘Solidarity’ moved between different clusters and layers of society, culture, politics and forms of organisation; it combined ordinary questions with exceptional claims, and in so doing it overcame both old and new forms of debate by blurring private and public issues.”

One of the most important messages of Belarusians today is this: the 2020 protests in Belarus and the torments suffered by Belarusian political prisoners and other groups who happened to be in the epicentre of state terror have not been in vain.The former political prisoner Olga Klaskovskaya spent more than two years in prisons and a labour colony; she recalls the importance in 2020 of maintaining the spirits of other political prisoners whenever she met them. “Even if the meeting was no more than a brief transfer in a mobile prison van, we would manage to exchange a few words and say the main thing. And the main thing was that we are together and we empathise. And that none of it has been in vain.”

Both in her interviews and now in her book Турэмныя дзённікі [“Prison Diaries”] Olga Klaskovskaya talks about the tactics of “weak resistance” in prisons and labour colonies; those tactics include supporting each other with friendly, psychological and legal aid. In addition there were a variety of strategies for looking after yourself and each other, helping us to feel full of vigour. Another form of this “weak strategy” of resistance was the manner in which Belarussian political prisoners demonstrated a sense of their own personal dignity during their so-called trials.

Especially with regard to the Belarusians who have left their country, we can now add to these strategies the task of documenting the crimes of the Belarusian regime and so act as the voices of Belarusian political prisoners, of not submitting to depoliticisation, i.e. Belarusians in the diaspora should continue to participate in every possible way in the actions and work of protodemocratic Belarusian structures, or at the very least to maintain (critical) attention to and interest in what they are doing.

This is how in April 2023 the wife of a political prisoner who lives in Minsk and wishes to remain anonymous described her experience in the website specialised on stories on political prisoners in Belarus Politzek: “The year 2020 hasn't disappeared. When I walk around the city and look at people, I think, ‘You all were at the Sunday marches!’ We were united and felt something incredible back then. Even though today we are all under occupation by our own government, our city remains the same. People support each other. There's a sense of camaraderie. It's just that today it happens not on the streets but in personal relationships, conversations, and different situations that occur with us. And it is precisely the support of such people that helps me endure the fact that my husband is in prison.”

The revolution of hope, or Towards a new revolution of change

The widespread demand for support of the political prisoners and for each other, and caring solidarity was demonstrated by the Marathon of Solidarity with Belarusian political prisoners “We care”, held in July this year, and which raised €550,000 for the former political prisoners and their families. The donations made with reference to the so-called “protest articles” (23.34 and others) of the Code of Administrative Law of the Republic of Belarus, and the comments from participants of the marathon show that it provided an opportunity for the participants to sense once again the spirit of broad, inclusive solidarity of 2020; this is still very important for them. At the same time, it is of course impossible, three years later, to draw strength solely from this spirit, especially in view of the new context that Russia has created with its aggressive war against Ukraine.

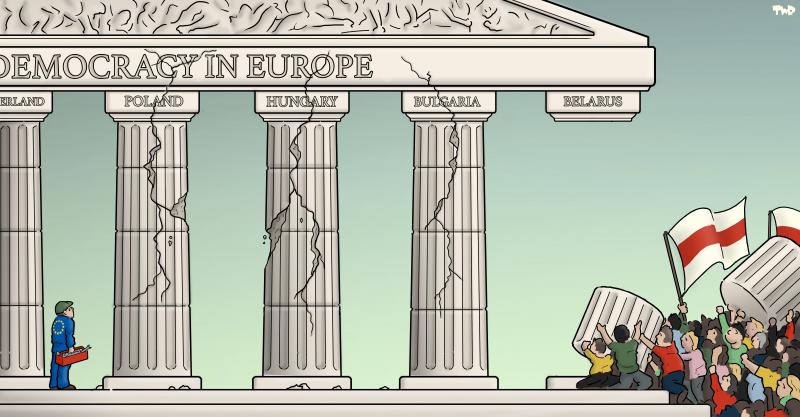

The Revolution of Change has been put on hold in Belarus until the next decisive moment. Meanwhile we have to make every effort to preserve the hope that the revolution will inevitably be continued. On the eve of the European Parliament elections, due to be held in 2024, a coalition of academics, artists, representatives of civil society and the public and private sectors, has also made a call for the “Revolution of Hope”. The reasons to come together and issue such a call are very much in accord with our Belarusian aspirations and experiences.

According to data provided by Eurobarometer, “the predominant feelings among Europeans today are uncertainty, frustration, helplessness, anger, fear – all feelings that fuel the division of the Union. For more than one in three Europeans, however, hope dwells among those predominant feelings. Not a hope made up of empty, dreamy waiting, but an active, purposeful hope”.

In 2020 we witnessed in Belarus a demand for democratic changes that encompassed huge sections of society. This demand gave birth to precisely that kind of hope in our country. We must now allow ourselves to be drawn along in its wake, to support whatever it is we do with a sense of solidarity, and to draw strength from caring support for each other.

👉 Original article on Reform.by

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!