This article is reserved for our subscribers

Quantifying the exact volume of illegally caught fish entering the European Union market poses a significant challenge. Illicit fishing can be difficult to detect, while illegal catches are disguised as legal ones. Although the EU is the largest seafood market in the world, importing more than 60 percent of its consumed seafood, one in six fish arriving in the Union are not traceable.

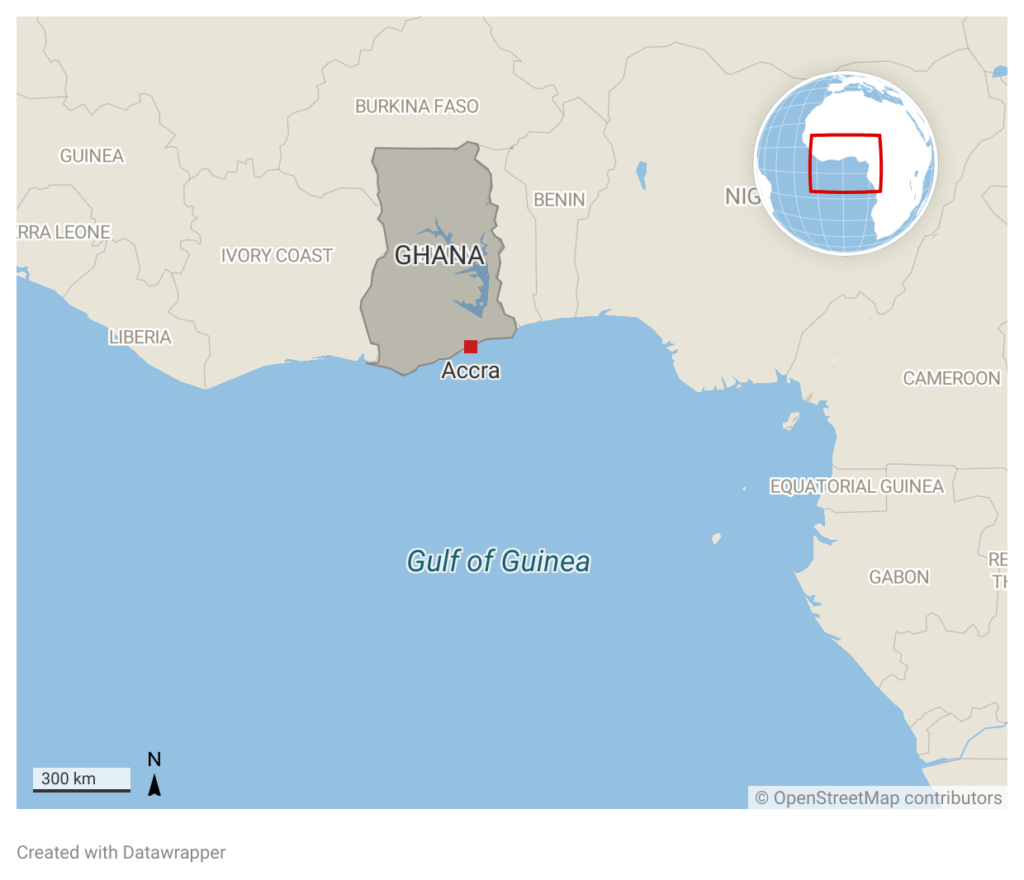

Each year, Ghana witnesses the illegal capture and trade of approximately 100,000 tonnes of small pelagic fish, primarily comprising sardinella, mackerel, and anchovies. A substantial portion of this catch is destined for export, including to the EU market. While small pelagic fish play a vital role in Ghana’s fishing industry – and thus its food security and national economy – their stocks have plummeted by approximately 80 percent over the past two decades. Without immediate action, the stocks’ complete collapse is expected in the coming years.

A major factor in this sharp decline is the illegal fishing carried out by industrial trawlers. Most vessels are owned by Chinese businesses “through opaque ownership arrangements.” Samuel-Richard Bogobley, an expert at Hen Mpoano, a nonprofit advocating for integrated management of coastal and marine ecosystems, explains that following Ghana’s ban on foreign trawlers, Chinese fishing firms started using Ghanaian companies as fronts. They would typically arrange phoney hire-purchase deals for Chinese-owned fishing vessels. Despite their unauthorised actions in Ghana, some of these companies possess EU export licences, legally allowing them to sell their products on the European market.

Ghana boasts around 200,000 artisanal fishers and approximately 300 landing sites. Marine fisheries serve as a livelihood for around 2.7 million people and contribute to the nation's food security. Artisanal fishermen primarily target small pelagic fish near the shore and in the open ocean's upper layers, accessible to their wooden canoes.

Although the Ghanaian government has taken some steps to combat illegal fishing, such as launching a web application to report it, it is not sufficient to reverse the trend. The EU could also contribute more.

How did the fish stocks decline so much?

In 2002, Ghana established an Inshore Exclusive Zone for artisanal fishers, aiming to protect stocks of small pelagic fish. Despite this, industrial vessels with licences for bottom-dwelling fish continued illegal fishing. Since they cannot bring back to the shore the captured small pelagic fish, the Chinese-owned companies sell it at sea to small artisanal fishers, who are legally allowed to fish it and bring it to land. This is done through a practice called saiko.

Bogobley explained that this allows the trawlers to bring only legal catches alongside a limited proportion of by-catches, including the small pelagic fish, thus meeting the Ghanaian port authorities’ landing requirements. The practice of saiko has “developed into an industry of its own,” he says, in which both the trawlers and the artisanal fishermen are active participants. The fish legally brought back by both trawlers and artisanal fishermen then gets shipped to the European market. Seemingly everything is in order.

While the majority of the businesses are Chinese-owned, European boats and operators are also involved in illegal activities in Ghana. European fishing vessels are difficult to trace, however, because they are often re-flagged to non-EU countries.

Vessel reflagging occurs for two main reasons: to secure fishing quotas from other states via Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) or to bypass fishing authorisation requirements in the waters of non-EU countries where sustainable fisheries agreements (SFPAs) exist. SFPAs are negotiated by the EU Commission. However, if a vessel is re-flagged to a non-EU country, an EU operator can set up a private agreement to continue fishing in SFPA-covered waters.

An example of re-flagging is the super-trawler Franziska, owned by the Dutch company Willem Van der Zwan en Zonen, which has a subsidiary in Ghana. This trawler has switched flags multiple times, going from Dutch to Peruvian between 2009 and 2013, before returning to the Dutch flag.

To make matters worse, the European trawlers are fuel-tax exempt, thus indirectly costing EU citizens funds that could be invested elsewhere, including in sustainable fisheries. From 2010 to 2020, the EU’s fishing fleet enjoyed a fuel-tax exemption of about €15.7 billion.