In purely geographical terms, the change of social system in Hungary has changed nothing: the country still covers an area of 93,000 km2. On the other hand, the former People’s Republic now borders five new countries that owe their statehood to the dissolution of larger, multi-ethnic entities. In the north, the border is no longer with the former ČSSR, Socialist Czechoslovakia, but with the Republic of Slovakia and with Ukraine, once part of the USSR but now independent.

To the south, the collapse of the former Yugoslavia has led to the creation of three new states: Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia. What connects most of these new political entities with Hungary and indeed its old neighbours, Romania and Austria, is the bid for EU membership. Serbia is on the waiting list, Ukraine is viewed as a desirable candidate.

Two of the successor states in the former Eastern bloc, Slovakia and Slovenia, have adopted the euro as their currency; Serbia and Croatia, by contrast, have created their own national currency.

In the 1990s, all these countries became parliamentary democracies in which the rivalries between the various power groups were played out openly and, not infrequently, violently. Every twist and turn and every internal conflict in these republics affects Hungary’s interests because of the Hungarian minorities living there: 1.5 million in Romania, 500,000 in Slovakia, 150,000 in Ukraine, 300,000 in Serbia, 16,000 in Croatia and 15,000 in Slovenia.

These minorities are a legacy of two post-war accords, the 1920 Treaty of Trianon and the 1947 Paris Peace Treaties, which entailed significant territorial losses for Hungary. Current problems faced by Hungarians abroad, be they to do with language rights or educational institutions, inevitably supply material for domestic politics too. Age-old animosities are resurrected again and again and are easily instrumentalised. Admittedly, some of Hungary’s neighbours cannot always resist such temptations either, but so far these conflicts have been kept within peaceful bounds and have only had an indirect impact on Hungary’s security interests. However, the Yugoslav wars of 1991-2001 revealed the fragile stability across the region as a whole and what happens when superpowers meddle in national disputes.

Interesting article?

It was made possible by Voxeurop’s community. High-quality reporting and translation comes at a cost. To continue producing independent journalism, we need your support.

24 February 2022 will undoubtedly go down in the annals of European and therefore also Hungarian history. Russia’s undeclared war in Ukraine has dramatically changed the relations that had prevailed between East and West since the collapse of the USSR, and cast an almost apocalyptic shadow over world politics. It is hard to predict when or how this armed conflict will end, but it will undoubtedly take a long time for a new peace-guaranteeing equilibrium to be established. At the very least, the European Union and NATO now have to reckon with a hostile power on their borders and prepare for a new phase of the Cold War.

In terms of how the devastating “special military operation” in Ukraine might have influenced the 3 April Hungarian election, it would seem logical to assume that, given the current atmosphere of fear, voters preferred to keep the single party Fidesz in power, rather than risk a shaky six-party coalition. This assumption also underlies PM Viktor Orbán’s openly stated desire for Hungary to be “exempted” from the conflict, a position that has been heavily criticised by the opposition and even condemned as a betrayal of Hungary’s western allies.

The proposed “exemption” is limited to two areas, however: the refusal to allow arms shipments destined for Kyiv to transit Hungarian territory, and the refusal to extend EU sanctions against Russia to the energy sector. This latter stance is intended to enable an already controversial Russian-Hungarian project to build a nuclear power plant on the Danube (Paks II) to go ahead unaltered.

Even though Hungary does have special interests that merit consideration, the request to be “exempted” clearly goes too far. Hungary has a 136 km border with Ukraine (the former border with the USSR) and, as stated above, there are roughly 150,000 ethnic Hungarians living in the Transcarpathian Oblast, many of them married to Ukrainians. Consequently, nearly 200,000 refugees – Hungarians, Ukrainians and even citizens of third countries resident in Ukraine – have so far entered Hungary via the six border crossings. Even if the majority of them do not intend to remain in Hungary, the logistical arrangements involved will have an enormous, unpredictable impact on national finances. Without the selfless assistance of civil organisations and private citizens, as well as EU support, it would be difficult to meet this challenge.

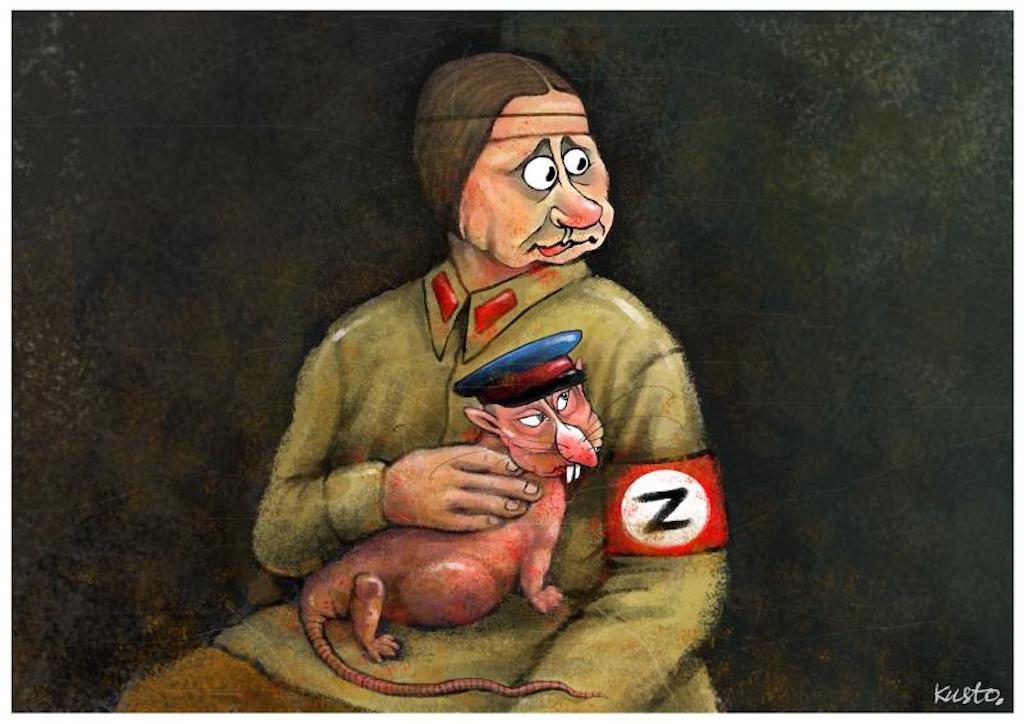

Orbán’s closeness to Putin is no mere coquetry but rather an integral part of the “special path” he is seeking to tread between East and West

Politically, too, the war raises awkward questions: Hungary’s relations with the two adversaries are far from equally balanced. In 1995, the government of József Antall signed a treaty of friendship with the independent republic of Ukraine that, among other things, guaranteed visa-free travel. Relations between the two countries cooled, however, largely due to Kyiv’s restrictive language policies, which adversely affect both the Hungarian and the enormous Russian minorities in Ukraine. At the same time, in the Orbán era relations with Putin’s Russia have positively blossomed as a result of the mental similarities between the two statesmen: the authoritarian posturing and the illiberalism underlying their respective concepts of the state.

Orbán’s closeness to Putin, most recently manifested in his visit to Moscow at the end of January 2022, which was hyped as a “peace mission”, is no mere coquetry but rather an integral part of the “special path” he is seeking to tread between East and West. Repeated lip service to fundamental European values and the signing of joint declarations against the Russian invasion do little to challenge the impression that, in the Orbán era, Hungary is increasingly drifting into mere corresponding membership of the EU.

While the horrific images of the war are continuing to shock the public day after day, and the end of the conflict, with all its devastating economic consequences, cannot be far off, the Hungarian prime minister preaches “strategic calm”. Whatever individual citizens may make of this rather nebulous concept, it may conceal the unease of the Fidesz elites. In the thirteenth year of the Orbán era, the system is facing increasing difficulties arising from its own economic and social policies. The national currency is losing value by the day (one euro currently costs 400 forints; in 2010 it was just 285) and food prices are soaring.

The government has imposed a temporary price freeze, a measure that is hitting small and micro businesses hardest and which, in the case of petrol prices, has forced many filling stations into bankruptcy due to falling revenues. Orbán tries to explain the 10.7% inflation rate in monocausal terms: “We have been able to stay out of the war, but we will not be spared its consequences. Prices are being driven upwards partly by the war, but partly also by the sanctions imposed by the West.” Viktor Orbán is clearly creating “strategic calm” for himself by shifting the responsibility for the financial crisis onto “the West”. It just remains to be seen how much longer a small country like Hungary, poor in both energy and raw materials, will be able to go on sitting on the fence.