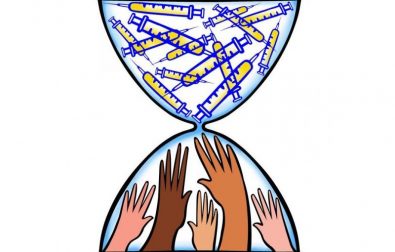

For thousands of undocumented migrants in Spain access to the vaccine is a complex and bureaucratic process that raises fears of deportation. The Spanish investigative NGO porCausa estimated in 2020 that between 390,000 and 470,000 people remained undocumented in the country, and that four in five of them were under the age of 40. Current estimates indicate that this number is likely higher, with up to half a million irregular migrants residing in the country. The study found that undocumented people were particularly at risk during the pandemic - both to a general lack of trust in the authorities, and to language barriers.

👉All the articles from this investigation

In Spain, a “popular legislative initiative” is underway which would force a parliamentary debate on the regularisation of undocumented people. One of the main arguments employed is the importance of equal access to the national healthcare system.

For Gonzalo Fanjul, porCausa’s head of research, “This is too big of an issue to be ignored. Access to Covid vaccination proves that the regularisation debate is about our interests as much as it is about the migrants’”.

Interesting article?

It was made possible by Voxeurop’s community. High-quality reporting and translation comes at a cost. To continue producing independent journalism, we need your support.

On a theoretical policy level, Spain included vulnerable groups in its vaccination programme. But as a country where much of the governing happens at the regional level, unclear communication strategies and differing practices left many undocumented people facing obstacles and delays.

For Misti, a 24-year-old Bangladeshi who has been in Spain for three years and remains undocumented, getting vaccinated was a lengthy process, he told the Spanish Radio Broadcaster, Cadena Ser. He was unable to download the app needed to book a vaccine appointment - and struggles to understand Spanish. Eventually, he heard of a local organisation in Madrid, Valiente Bangla, that helps undocumented people to get the vaccine. He has since been able to get two doses, but is still unable to access the rest of the healthcare system.

Spain’s uneven performance during the pandemic was captured in a major survey by Lighthouse Reports, an investigative nonprofit newsroom working with leading European media outlets. Spain ranked as “Confused” with a weak policy score that lagged behind neighbouring Portugal. The scorecard found evidence of inclusive language in policy documents, but this was not echoed in public declarations made by health officials. Overall, it was unclear whether undocumented people had equal access to vaccination and whether getting the jab was possible without an ID.

Analysing public policies and communication has been key to understanding whether those most vulnerable have been accounted for. Francesca Pierigh, who coordinated Lighthouse’s investigation, said that Spain’s efforts were hampered by a lack of clarity. “At the national level, the policies and the language of these policies was so vague and unclear that it left too much to interpretation. For countries scored as Confused, which include Spain, it means that we were not able to score them, or to say if there has been an effective inclusion or exclusion of the undocumented.”

Spain’s vaccination protocol initially prioritised people in extreme vulnerability, including those living in overcrowded homes, homeless people, and the immunocompromised. For some undocumented people who are not registered in the national health system, setting up a vaccination appointment proved a challenge. “Because they are not registered, the system does not proactively call them, and does not vaccinate them,” said Nives Turienzo, president of the Doctors of the World, a medical charity.

Part of the lack of clarity around Spain’s vaccination process for the undocumented comes from the variation in approaches taken by different regions.

Some regional strategies have fared better than others. Vaccinations without appointment were successful in reaching more people, as opposed to systems that required booking. For its part, Doctors of the World has been working in 14 regions, often organising vaccination drives in partnership with health centres. Some regions facilitated open-doors policies, allowing people to get vaccinated without a health card – but heavy bureaucracy in other regions left many behind. In the region of Madrid, there are still people waiting for their first vaccination. Difficulties in accessing the booster are also common, said Turienzo.

Elahi Fazle, the leader of the grassroots organisation Valente Bangla, has spent the past year helping undocumented migrants access the Covid-19 vaccine. For Fazle, language barriers are a major issue raised by the people he supports – particularly as the online service designed to set up vaccine appointments displays only Spanish. Internet access is another important obstacle, since many people are unable to pay for an internet connection and are not familiar with navigating online portals. Since the summer of 2021, the organisation has helped 1,400 people access the vaccine – assisting people in setting up their appointments, and accompanying them when they do not speak the language. Valente Bangla also offers Spanish courses for undocumented migrants.

Fear remains another major obstacle for many undocumented people. Although Lighthouse’s analysis gave Spain a positive score on privacy guarantees for undocumented people who try to get vaccinated, many people are still reticent to share their personal information, fearing that this may jeopardize their stay in the country. “People fear deportation because they have seen it happening to others, and they see the cost of this. Some take years to reach Europe, they won’t risk it all to go to a place where they will be asked for personal information that can locate them. They are scared”, said Turienzo.

For some, this means living with stigma. “Sometimes I’m on the bus, and because I am an immigrant, I can see some people are fearful, they might think I am undocumented, or that I am not vaccinated yet”, said Mohamed Eli, who is now regularised but described a complicated process to access vaccination.

Across Spain, organisations like Doctors of the World continue to work with local communities in attempts to facilitate vaccine access. “We try to make a bit of a fuss in every community we are in”, Turienzo said. “Those who govern us need to be reprimanded”.

👉 The programme on Cadena Ser