“At first I thought they were experimenting on us, I didn't want to get vaccinated,” says Katy. "But then I realised it was necessary, for me and for my family."

The setting is one of the huge Cinecittà film studios on the outskirts of Rome, where some of Italy’s most iconic movies were made. In 2021 it was converted into a Covid-19 vaccination centre, so Katy (not her real name) is not here for an audition, but to get back to a more normal life. “I can’t wait to get my green pass [the vaccine certificate], be able to use public transport again and go looking for a job,” says the dark-haired Peruvian. She wants to escape the silent corridors and overcrowded rooms of the squat on Via Sambuci where she lives, even if just for a few hours. Ever since the start of the pandemic she has been confined to a 30m2 apartment, which she shares with her three children, husband, mother and mother-in-law.

👉All the articles from this investigation

But according to the health ministry, she does not exist, or at least not under the data used for her vaccination. Since she had no residence documents, Katy booked her vaccination using an STP code (Straniero temporaneamente presente, “temporarily resident non-national”), a kind of temporary health card, valid for six months, which is supposed to guarantee universal access to the healthcare enshrined in the Italian constitution, even for undocumented migrants, whether long-term or temporary.

In 2020 Katy gave birth for the third time, this time in Italy. This allowed her to obtain a residence permit on the basis of maternity and, with that, a tax code. That piece of paper, valid for six months, is "the only document I've had in more than four years in Italy", she says.

Once that permit expired, she lost her immigration status, despite the fact that her two children were attending school and both she and her husband had been working. The only way she could get vaccinated was with an STP code; but in the national health database her name was still listed with the tax code she had been given after the birth of her child. The two sets of data did not match. It took four months, from September 2021 to January 2022, and the intervention of the humanitarian organisation Intersos before she was finally able to access her vaccination certificate.

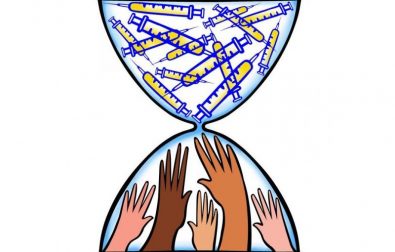

Katy is far from alone in facing these difficulties. Humanitarian workers, doctors and public officials confirm that for the 500,000-plus non-nationals without official status in Italy – the ISMU Foundation puts the number at 517,000 as at January 2020 – getting vaccinated has been, and continues to be, an obstacle course. The same applies to obtaining the vaccine certificate that has been a prerequisite for accessing a number of basic services since August 2021.

The European investigative nonprofit newsroom Lighthouse Reports spent six months collecting and analysing public documents to assess the transparency of government policies, privacy safeguards and vaccine access requirements for millions of undocumented individuals in 18 European countries.

Their report rated Italy’s response as "confused" on the basis of a lack of data, a lack of clear and binding requirements on the documentation required to access the vaccine, and a lack of a dedicated budget for the vaccination of undocumented individuals. Only Portugal, the Netherlands, Ireland, France and the United Kingdom were considered "open and accessible", while Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic were rated "closed and exclusionary".

According to Alessandro Verona, medical coordinator of the NGO Intersos, which provides health services to people like Katy who are excluded from the national health system, "the tools were there, but either there was no willingness to use them or the actions were taken too late". He cites a document circulated as early as 2020 by the National Institute for Health, Migration and Poverty, part of the Ministry of Health. This document provided guidelines for the management of facilities for people experiencing acute socio-medical marginalisation, but Verona says they have been "largely disregarded".

Not until the end of August 2021 – eight months after the start of the vaccination campaign – did the then Special Commissioner for the COVID-19 Emergency, Francesco Paolo Figliuolo, write to the regions and provinces to push for "people who are experiencing particular hardship or who are not currently covered by the national health card” to be vaccinated using the STP, the temporary health code for undocumented, non-EU non-nationals. Even then, the letter did not set out clear criteria for accessing vaccines and vaccine certificates.

"We needed a unified approach, but instead everything was left to the local authorities, which resulted in a mix of good practice and discrimination," says Verona. He believes that the gulf between the authorities and already marginalised groups was widened by the absence of cultural mediators in healthcare facilities, along with vaccination booking platforms that were often complex and only available in Italian.

Katy’s experience is far from unique among her neighbours in the squat. In 2020 Elizabeth, 50, from Ecuador, was unable to renew her residence permit for work purposes owing to a clause in a 2014 law that prevents people from registering if they are living in an illegally occupied building. The tiny room where she had been living for eight years was no longer recognised as a home. She became undocumented at the start of the pandemic, despite having spent years working as a maid, bartender and cleaner, and was only finally able to renew her residence permit in December 2021.

Getting vaccinated in the midst of this bureaucratic limbo took months and two periods of isolation for Covid-19, which she spent in a room in the squat set aside for those who tested positive. The local health services turned her away several times. They told her to renew her health card, but this was tied to her residence permit – which was still pending. Elizabeth finally received her first vaccine dose in October 2021.

"We needed a unified approach, but instead everything was left to the local authorities, which resulted in a mix of good practice and discrimination."

Alessandro Verona, medical coordinator of the NGO Intersos

This long wait has been shared by many of the 207,000 foreign workers who applied for regularisation in 2020 under an amnesty that the then Minister for Agriculture and Forestry, Teresa Bellanova, had proclaimed as an "historic achievement". As of the beginning of November 2021 only 27,000 permits had been issued from a total of about 70,000 applications received.

Lubomira, 58, from Ukraine, has been waiting for a residence permit for almost two years. She lives in a middle-class district of Rome. In the evenings she acts as carer for the 81-year-old owner of the house, and during the day she works as a cleaner in other apartments in the city. These days she spends her nights on the phone to her 30-year-old son, who is still in western Ukraine. From October to early February, however, she found herself effectively locked inside her home: "The local authorities told me I had to have a tax code in order to get vaccinated, but they wouldn't accept the temporary one I was given by the Internal Revenue Service after I applied for regularisation in 2020." Despite technically being a regular migrant, since her application for a residence permit was being assessed, she was only able to get vaccinated in January 2022, using an STP code.

Paolo Parente, director of Roma 1, a local health service covering one third of the population of the Italian capital, admits that "there have been several obstacles, especially with issuing certificates", but puts this down partly to the initial lack of "legal directives to vaccinate these categories of people". He says Roma 1 overcame these obstacles by "getting civic organisations involved and opening dedicated vaccine hubs".

As of 20 February 2022, 7125 STP code holders had been vaccinated in the area covered by Roma 1, but at the national level there is no data available. The health ministry has not responded to requests from our network of journalists.

The Lombardy region, which has been hit hardest by the pandemic, has vaccinated only 33,000 people with STP codes. Organisations working there report a lack of political will on the part of the regional authorities. "Without the civic sector, no irregular migrants would even have been vaccinated in Lombardy, let alone obtained a green pass,” says Anna Spada from Naga, a voluntary organisation assisting irregular foreigners and homeless people in Milan. “We have helped people who are already living on the margins to overcome absurd bureaucratic hurdles."

👉 Original article at Domani

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!